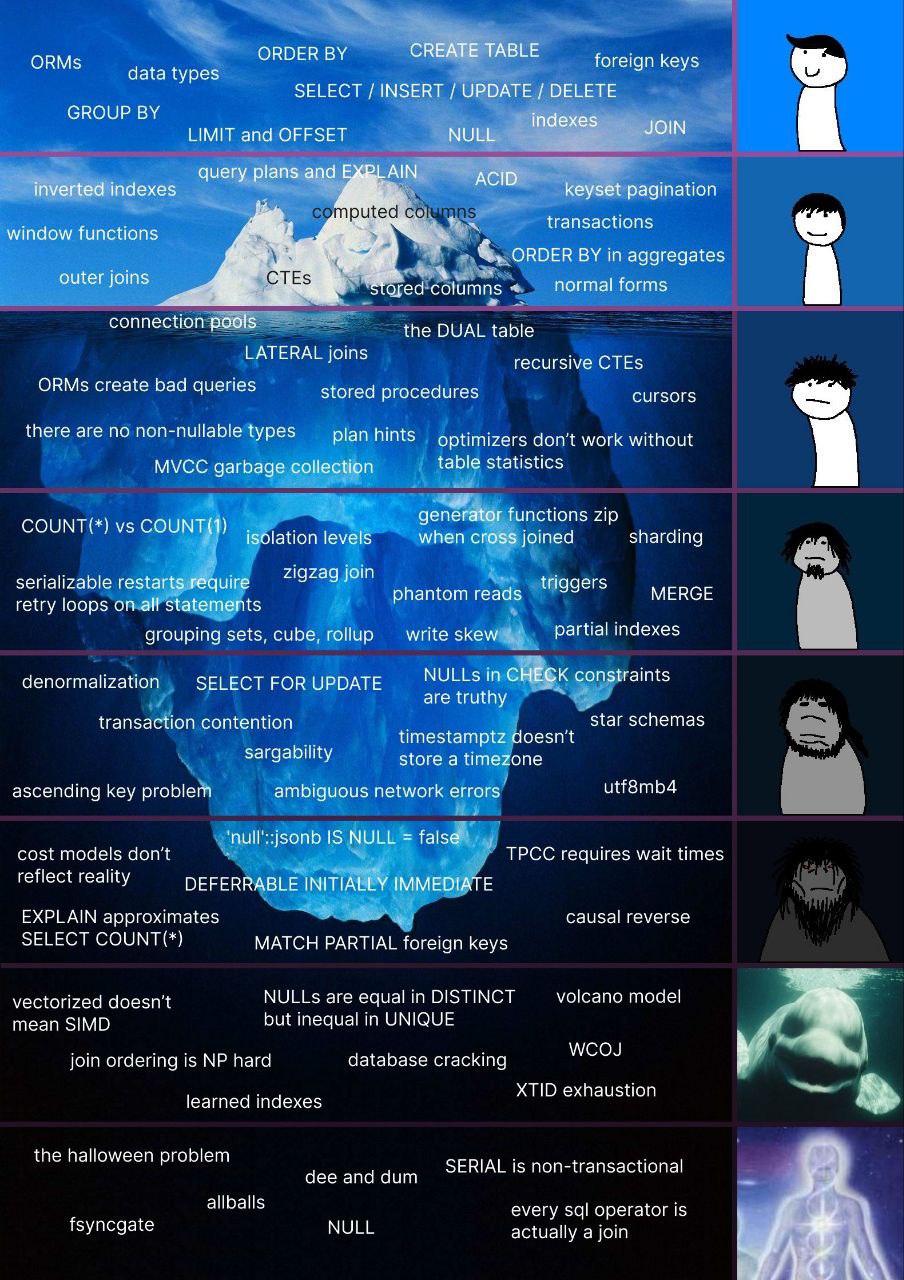

I spend a significant amount of my time online, and on a regular day, I am either learning about STEM topics, indulging in memes, or both. On one such day, I came across a meme that truly caught my attention. It sparked numerous questions above my head, leading to a moment of deafening silence within me:

I already knew that data storage and retrieval ain't ever been one of my strong suits, but after seeing this meme it kind of made me unsecure as I had basically zero effing clue about a huge portion of it. I felt the urge that I have to know what this is all about, so I have decided to learn from multiple sources.

One of the best ways to learn something is to explain it, and this blog post aims to do exactly that. Let's review and explain every part of this meme, while unraveling its meaning and secrets.

Levels

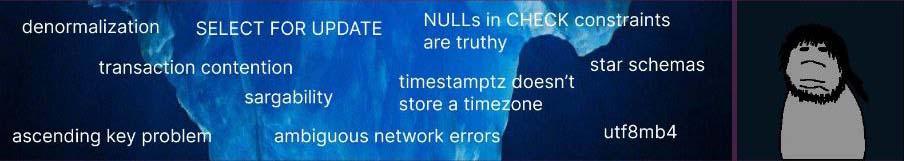

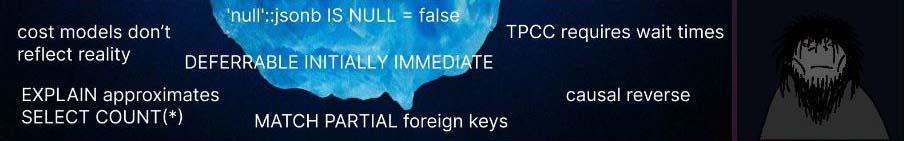

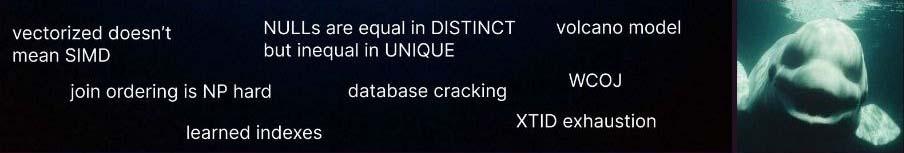

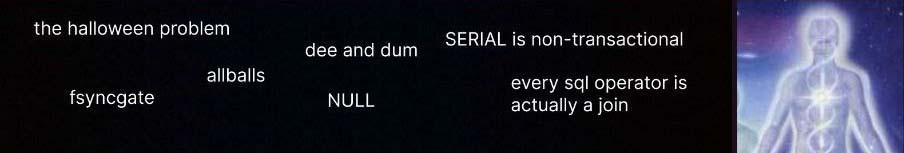

Let's name each level in the meme:

- Level 0: Sky Zone:

CREATE TABLE,JOIN,NULL, ... - Level 1: Surface Zone: ACID, outer joins, normal forms, ...

- Level 2: Sunlight Zone: Connection pools, LATERAL Join, Stored Procedures, ...

- Level 3: Twilight Zone: Isolation levels, ZigZag Join, Triggers, ...

- Level 4: Midnight Zone: Denormalization,

SELECT FOR UPDATE, star schemas, ... - Level 5: Abyssal Zone:

MATCH PARTIALforeign keys,'null'::jsonb IS NULL = false, ... - Level 6: Hadal Zone: volcano model, join ordering is NP Hard, ...

- Level 7: Pitch Black Zone:

NULL, the halloween problem, fsyncgate, ...

Level 0: Sky Zone

Welcome to Sky Zone! These are the very high level concepts which everyone seem to have encountered while working with Relational Database Management Systems like PostgreSQL. Without any further ado, let's get into the topics on the sky level.

Data Types

PostgreSQL supports a large number of different data types varying from numeric, monetary, arrays, json, and xml to things like geometric, network address, and composite types. Here is a long list of supported data types is PostgreSQL.

This query shows the types that are interesting to an application developer. It results 87 different data types on PostgreSQL version 14.1:

select typname, typlen, nspname

from pg_type t

join pg_namespace n

on t.typnamespace = n.oid

where nspname = 'pg_catalog'

and typname !~ '(^_|^pg_|^reg|_handlers$)'

order by nspname, typname;

As an example, if you want to store the audit logs of the actions done by admin users and

need to store their IPs, you can use the inet type in PostgreSQL instead of storing it as text.

This will help you to store those data more efficiently, and validate them more easily, compared

to a system that doesn't support such a type (e.g. Sqlite).

CREATE TABLE

SQL (Structured Query Language) is composed of several areas, and each of them has a specific sub-language.

One of these sub-languages is called DDL which stands for data definition language. It consists of

statements like CREATE, ALTER, and DROP, which are used to defined on-disk data structures.

Here is an example of a create table query:

create table "audit_log" (

id serial primary key,

ip inet,

action text,

actor text,

description text,

created_at timestamp default NOW()

)

This will create an audit_log table with columns such as id, ip, action, etc.

SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE

DML is another one of SQL sub-languages and stands for data manipulation language. It

covers the insert, update, and delete statements which are used to feed data into the

database system.

select also helps us to retrieve data from the database. This is probably one of the simplest

select queries in SQL:

select 0;

Here are some of the examples of such DML queries:

insert into "audit_log" (ip, action, actor, description) values (

'127.0.0.1',

'delete user',

'admin',

'admin deleted the user x'

)

The table table_name command can also be used to select an entire table. This sql command:

table users;

is equivalent to

select * from users;

ORDER BY

SQL does not guarantee any kind of ordering of the result set of any query, unless you specify an

order by clause.

select *

from "audit_log"

order by created_at desc;

LIMIT and OFFSET

LIMIT and OFFSET allow you to retrieve just a portion of the rows that are generated

by the rest of the query. The below query returns audit logs number 100 to 109:

select *

from "audit_log"

offset 100

limit 10;

GROUP BY

The group by clause introduces Aggregates (aka Map/Reduce) in PostgreSQL, which enables us to

map our rows into different groups and then reduce the result set into a single value.

Assuming we have a Student table definition with id, class_no and grade columns, we can

find the average grade of each class using this query:

select class_no, avg(grade) as class_avg

from student

group by class_no;

Note that the Student table defined this way for demonstration purposes only.

NULL

In PostgreSQL, NULL means undefined value, or simply not knowing the value, rather than the absence of a value.

That is why true = NULL, false = NULL, and NULL = NULL checks all result in a NULL.

select

true = NULL as a,

false = NULL as b,

NULL = NULL as c;

-- result

-- a = NULL

-- b = NULL

-- c = NULL

Now that you know the meaning of NULL, you should be more careful with its semantics. The following

query returns no rows:

select x

from generate_series(1, 100) as t(x) -- `generate_series(1, 100)` creates rows 1,2,3,...,99,100

where x not in (1, 2, 3, null)

-- total rows: 0

Indexes

When used correctly, Indexes in PostgreSQL allow you to access your data much faster

because they prevent the need for a sequential scan when an index is present.

Additionally, certain constraints like PRIMARY KEY and UNIQUE are only possible

using a backing index.

Here is a simple query to create an index on last_name column of student table

using GiST method.

create index on student using gist(last_name);

An index cannot alter the result of a query. It duplicates data to optimize searches, hence why each index adds write costs to your DML queries. Therefore, it is not a good idea to put index on everything even if you have infinite storage. You will still need to pay the maintenance cost of indexes.

JOIN

Queries can access multiple tables at once, or access the same table in such a way that multiple rows of the table are being processed at the same time. Queries that access multiple tables (or multiple instances of the same table) at one time are called join queries.

We can also see joins as a way to craft new Relations from a pair of existing ones. A relation in PostgreSQL is a set of data having a common set of properties.

The simple query below retrieves the admin user with its role name:

select u.username, u.email, r.role_name

from "user" as u

join "role" as r

on u.role_id = r.role_id -- equivalent: using(role_id)

where u.username = 'admin';

There are multiple kinds of joins, including but not limited to:

- Inner Joins: Only keep the rows that satisfy the join condition for both side of involved relations (left and right).

- Left/Right/Full Outer Joins: Retrieve all records from table even for those with no matching value in either left, right, or both side of the relations.

- Cross Join: A cartesian product of left and right relations, giving all the possible combinations from the left table rows joined with the right table rows.

There are also some other types of joins which we will discuss in deeper levels.

Foreign Keys

Foreign key constraints help you to maintain the referential integrity of your data.

Assuming you have Author and Book tables, you can reference Author from the Book

table, and PostgreSQL will make sure that the referencing author exists in the Author table

when inserting a row into the Book table:

create table author (

name text primary key

);

create table book (

name text primary key,

author text references author(name)

)

insert into author values ('George Orwell');

insert into book values ('Animal Farm', 'George Orwell'); -- OK

insert into book values ('Anna Karenina', 'Leo Tolstoy'); -- NOT OK

-- ERROR: insert or update on table "book" violates foreign key constraint "book_author_fkey"

-- DETAIL: Key (author)=(Leo Tolstoy) is not present in table "author".

PostgreSQL enforces the presence of either a unique or primary key constraint on the

target column of the target table.

ORMs

Object-relational Mapping (ORM, O/RM, and also known as O/R Mapping tool) is a technique for mapping data to and from relational databases and an object-oriented programming language. ORMs help programmer to interact and alter the data within the database using the language constructs defined in an object-oriented programming language. In other words, ORM acts as a bridge between the object-oriented world, and the mathematical relational world.

// Java, Hibernate ORM

@Entity

@Table(name = "Person")

public class Person {

@Id

@GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

private Long id;

private String name;

private int age;

}

Configuration configuration = new Configuration().configure("hibernate.cfg.xml");

SessionFactory sessionFactory = configuration.buildSessionFactory();

try (Session session = sessionFactory.openSession()) {

List<Person> persons = session.createQuery("FROM Person", Person.class).list();

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

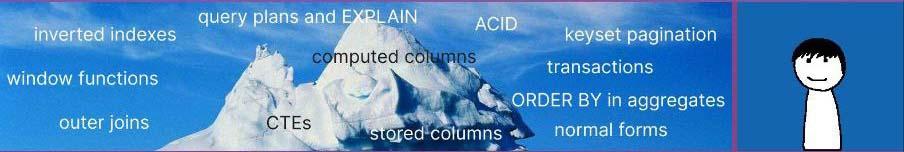

Level 1: Surface Zone

Welcome to Surface Zone! Now that we have got past the sky level, we can get familiar with some of the more advanced features and concepts and dive deeper into the fundamental components and functionalities of PostgreSQL . These topics will give you a solid grounding and understanding of the database system.

Transactions

A transaction turns a bundle of steps/actions into a single "all or nothing" operation. The intermediate steps are not visible to other concurrently running transactions. Generally speaking, a transaction represents any change in a database.

In PostgreSQL, a transaction is surrounded by BEGIN and COMMIT commands.

PostgreSQL treats every SQL statement as being executed within a transaction.

If you do not issue a BEGIN command, then each individual statement has an implicit BEGIN

and (if successful) COMMIT wrapped around it. The below example

shows transferring of a coin from Player1 to Player2 in the database of a video game server

(the example is oversimplified):

BEGIN;

update accounts set coins = coins - 1 where name = "Player1";

update accounts set coins = coins + 1 where name = "Player2";

COMMIT;

Here we want to make sure that either all the updates are applied to database, or none of them happen. We do not want a system failure decrease coins from Player1, but no coin is added to Player2's inventory. Grouping a set of operations into a transaction gives us such guarantee.

ACID

ACID is an acronym for Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability. These are a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps.

A database transaction should be ACID by definition:

- Atomicity: A transaction must either be complete in its entirety, or have no effect. Atomicity guarantees that each transaction is treated as a single "unit".

- Consistency: Ensures that a transaction can only bring the database

from one consistent state to another, and prevent database corruption by an illegal transaction.

As an example, a transaction should not allow a

NOT NULLcolumn to have aNULLvalue after aCOMMIT. - Isolation: Transactions are often executed concurrently (multiple reads and writes at a time). As we have stated in the previous section, the intermediate steps are not visible to other concurrently running transactions, which means a concurrently executed transaction shouldn't have a different result compared to when the transactions were executed sequentially.

- Durability: The database management system is not allowed to miss any committed transaction after a restart or any kind of crash. All the committed transactions should be written on non-volatile memory.

Query plans and EXPLAIN

Every database system needs a planner to create a query plan out of your SQL queries.

A good query planner is critical for good performance. In PostgreSQL, the EXPLAIN command is

used to know what query plan is created for the input query.

explain select "name", "author" from "book";

-- output:

-- Seq Scan on book (cost=0.00..18.80 rows=880 width=64)

For a more complex query like this:

select

w.temp_lo,

w.temp_hi,

w.city,

c.location as city_location

from weather as w

join city as c

on c.name = w.city;

We get more information on things like how is PostgreSQL trying to find the record

(using a sequential scan or hash, etc), costs, timing, and performance information.

Below information is obtained using EXPLAIN ANALYZE command. Using ANALYSE option alongside

EXPLAIN shows the exact row counts and true run time along with estimates provided by the

EXPLAIN:

[

{

"Plan": {

"Node Type": "Hash Join",

"Parallel Aware": false,

"Async Capable": false,

"Join Type": "Inner",

"Startup Cost": 18.10,

"Total Cost": 55.28,

"Plan Rows": 648,

"Plan Width": 202,

"Actual Startup Time": 0.024,

"Actual Total Time": 0.027,

"Actual Rows": 3,

"Actual Loops": 1,

"Inner Unique": false,

"Hash Cond": "((w.city)::text = (c.name)::text)",

"Plans": [

{

"Node Type": "Seq Scan",

"Parent Relationship": "Outer",

"Parallel Aware": false,

"Async Capable": false,

"Relation Name": "weather",

"Alias": "w",

"Startup Cost": 0.00,

"Total Cost": 13.60,

"Plan Rows": 360,

"Plan Width": 186,

"Actual Startup Time": 0.010,

"Actual Total Time": 0.010,

"Actual Rows": 3,

"Actual Loops": 1

},

{

"Node Type": "Hash",

"Parent Relationship": "Inner",

"Parallel Aware": false,

"Async Capable": false,

"Startup Cost": 13.60,

"Total Cost": 13.60,

"Plan Rows": 360,

"Plan Width": 194,

"Actual Startup Time": 0.008,

"Actual Total Time": 0.008,

"Actual Rows": 3,

"Actual Loops": 1,

"Hash Buckets": 1024,

"Original Hash Buckets": 1024,

"Hash Batches": 1,

"Original Hash Batches": 1,

"Peak Memory Usage": 9,

"Plans": [

{

"Node Type": "Seq Scan",

"Parent Relationship": "Outer",

"Parallel Aware": false,

"Async Capable": false,

"Relation Name": "city",

"Alias": "c",

"Startup Cost": 0.00,

"Total Cost": 13.60,

"Plan Rows": 360,

"Plan Width": 194,

"Actual Startup Time": 0.004,

"Actual Total Time": 0.005,

"Actual Rows": 3,

"Actual Loops": 1

}

]

}

]

},

"Triggers": [

]

}

]

If you have pgAdmin installed, it can show you a graphical output as well:

Inverted Indexes

An inverted index is an index structure storing a set of (key, posting list) pairs, where

posting list is a set of row IDs in which the key occurs.

Inverted indexes are used when we want to index composite values (called an item), where each element value in the item is a key. As an example, a document is an item, and the word we're searching for inside the document is the key.

PostgreSQL supports GIN, which stands for Generalized Inverted Index. GIN is generalized in the sense that the GIN access method code does not need to know the specific operations that it accelerates.

Keyset Pagination

There are many ways in which one can implement pagination to read only a portion of

the rows from the database. As we have suggested in the OFFSET/LIMIT section,

in many cases using offset will slow down the performance of your query as the database

must count all rows from the beginning until it reaches the requested page. One way to

overcome this is to use the Keyset pagination:

select *

from "audit_log"

where created_at < ?

order by created_at desc

limit 10; -- equivalent standard SQL: fetch first 10 rows only

Here instead of skipping records, we simply use keyset_column > x where x is the last record

from the previous page we have fetched.

- Read more: Paging Through Results by Markus Winand

Computed Columns

A computed or a generated column in a table is a column which its value is a function of

other column in the same row. In other words, a computed column for columns is what a view

is for tables. The value of a

computed column can be read, but it can not be directly written.

A computed/generated column is defined using GENERATED ALWAYS AS in PostgreSQL:

create table people (

...,

height_cm numeric,

height_in numeric GENERATED ALWAYS AS (height_cm / 2.54) -- this won't work, will explain why in the next section

)

Stored Columns

A generated column can either be stored or virtual:

- Stored: computed when it is written (inserted or updated) and occupies storage as if it were a normal column

- Virtual: occupies no storage and is computed when it is read

Thus, a virtual generated column is similar to a view and a stored generated column is similar to a materialized view (except that it is always updated automatically).

If you have tried the previous query you might have faced an error. This is because at

the time of writing this post PostgreSQL only implements stored generated columns, therefore

you need to mark the column using STORED:

create table people (

...,

height_cm numeric,

height_in numeric GENERATED ALWAYS AS (height_cm / 2.54) STORED -- works fine

);

ORDER BY Aggregates

An aggregate function computes a single result from a set of input values. Some of the most

famous aggregate functions are min, max, sum, and avg which are used to calculate

minimum, maximum, sum, and the average of a set of results. The query below calculates

the average of high and low temperatures from the weather records in the weather table:

select

avg(temp_lo) as temp_lo_average,

avg(temp_hi) as temp_hi_average

from weather;

The input of some aggregate functions are introduced by ORDER BY.

These functions are sometimes referred to as “inverse distribution” functions. As an

example, the below query shows the median rank of all players for each game server:

SELECT

"server",

percentile_cont(0.5) WITHIN GROUP (ORDER BY rank DESC) AS median_rank

FROM "player"

GROUP BY "server"

-- server median_rank

-- asia 2.5

-- europe 5

Window Functions

Window Functions are very powerful tools that let you process several values of the result set at a time. This might be similar to what we can achieve with aggregate functions, however, window functions do not cause rows to become grouped into a single output row like non-window aggregate calls would.

A window function call always contains an OVER clause directly following the

window function's name and argument(s):

select

city,

temp_lo,

temp_hi,

avg(temp_lo) over (partition by city) as temp_lo_average,

rank() over (partition by city order by temp_hi) as temp_hi_rank

from weather

-- city temp_lo temp_hi temp_lo_average temp_hi_rank

-- Lahijan 10 20 10.33333333 1

-- Lahijan 11 25 10.33333333 1

-- Lahijan 10 20 10.33333333 3

-- Rasht 15 45 15 1

-- Rasht 20 35 15 2

-- Rasht 10 30 15 3

When using Window Functions, understanding the concept of window frame is necessary. For each row, there is a set of rows within its partition called its window frame. Some window functions act only on the rows of the window frame, rather than of the whole partition.

In general, these are the window frame rules of thumb:

- If

ORDER BYis supplied then the frame consists of all rows from the start of the partition up through the current row (plus any following rows that are equal to the current row according to theORDER BYclause) - When

ORDER BYis omitted the default frame consists of all rows in the partition

select salary, sum(salary) over () from empsalary;

-- salary | sum

-- --------+-------

-- 5200 | 47100

-- 5000 | 47100

-- 3500 | 47100

-- 4800 | 47100

-- 3900 | 47100

-- 4200 | 47100

-- 4500 | 47100

-- 4800 | 47100

-- 6000 | 47100

-- 5200 | 47100

-- (10 rows)

Outer Joins

As we have mentioned earlier, an outer join retrieve all records from table even for those with no matching value in either left, right, or both side of the relations.

select *

from weather left outer join cities ON weather.city = cities.name;

-- city | temp_lo | temp_hi | prcp | date | name | location

-- ---------------+---------+---------+------+------------+---------------+-----------

-- Hayward | 37 | 54 | | 1994-11-29 | |

-- San Francisco | 46 | 50 | 0.25 | 1994-11-27 | San Francisco | (-194,53)

-- San Francisco | 43 | 57 | 0 | 1994-11-29 | San Francisco | (-194,53)

-- (3 rows)

Above query shows a left outer join because the table mentioned on the left of the join operator (weather) will have each of its rows at least once in the output, whereas the table on the right (cities) will only have those rows that match a row on the left table.

In PostgreSQL, left outer join, right outer join, and full outer join are used to do outer joins.

CTEs

WITH queries, or Common Table Expressions (CTEs) can be thought of as defining

temporary tables that exist just for one query. Using a WITH clause, we can define an

auxiliary statement which can be attached to a primary statement.

In the query below, we first define two auxiliary tables called hottest_weather_of_city, and

not_so_hot_cities, and then we use them in the primary select query:

with hottest_weather_of_city as (

select city, max(temp_hi) as max_temp_hi

from weather

group by city

), not_so_hot_cities as (

select city

from hottest_weather_of_city

where max_temp_hi < 35

)

select * from weather

where city in (select city from not_so_hot_cities)

In short, Common Table Expressions is just another name for WITH clauses.

Normal Forms

Database normalization is the process of structuring a relational database in accordance with a series of so-called normal forms to reduce data redundancy and improve data integrity.

There are several levels of normalization, and a higher level of database normalization cannot be achieved unless the previous levels have been satisfied.

Here are some of the normal forms:

- 1NF: Columns cannot contain relations or composite values (each cell is single-values), and there are no duplicated rows in the table

- 2NF: Non-key columns are dependent on all of the key (it should not be dependent on a part of the composite key). In other words, there are no partial dependencies.

- 3NF: Table has no transitive dependencies.

Other normals forms like EKNF, BCNF, 4NF, 5NF, DKNF, and 6NF are not covered in this blog post. You can read more about them at the Wikipedia page of normal forms.

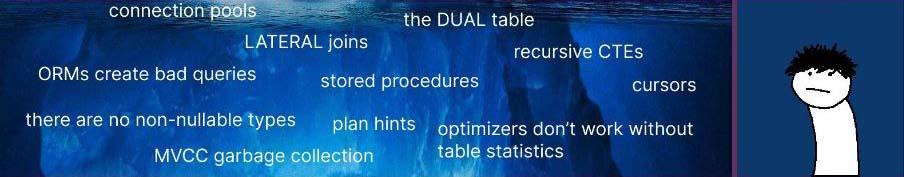

Level 2: Sunlight Zone

Welcome to Sunlight Zone! As we descend further, we'll explore more advanced features and techniques in PostgreSQL. Get ready to bask in the glow of knowledge and expand your database skills.

Connection Pools

Connecting to a database server consists of several time-consuming steps (create a socket, initial handshake, parse connection string, authentication, etc). Connection pools are a way to further improve performance by pooling users’ connections to a database. The idea is to decrease the total number of connections that must be opened. Whenever a client wants to connect to the database, an open connection from the pool is reused instead of creating a new one.

There are many tools and libraries for different programming languages which can help

you create connection pools, as well as server-side connection pooling software

that works for all connection types, not just within a single software stack.

You can create or debug connection pools with tools like Amazon RDS Proxy, pgpool, pgbouncer, pg_crash, etc.

The DUAL Table

The DUAL table is a single-row single-column dummy table which was initially added

as an underlying object in the Oracle database systems by Charles Weiss. This table is used

for situations when you want to select something but no from clause is needed.

In Oracle, FROM clause is mandatory, so you would need the dual table. However, in PostgreSQL, creating

such table is not required as you can select without a from clause.

--- postgresql

select 1 + 1;

-- oracle

select 1 + 1 from dual;

That being said, this table can be created in postgres as a view to ease porting problems from Oracle to PostgreSQL. This allows code to remain somewhat compatible with Oracle SQL without annoying the Postgres parser:

create table dual();

LATERAL Joins

PostgreSQL added the LATERAL join technique since PostgreSQL 9.3. Using lateral joins, you can look at the left hand table:

select * from weather as w

join lateral (

select city.location

from city

where city.name = w.city -- only possible to reference "w" because of lateral

) c on true;

In the above query, the inner subquery became a correlated subquery to the outer select query.

Without lateral, each subquery is evaluated independently and as a result, cannot cross-reference any

other FROM item. You would get this error if you haven't used LATERAL:

ERROR: invalid reference to FROM-clause entry for table "w"

HINT: There is an entry for table "w", but it cannot be referenced from this part of the query.

Recursive CTEs

WITH clauses can be used with the optional RECURSIVE option.

This modifier changes WITH from a mere syntactic convenience into a feature that accomplishes

things not otherwise possible in standard SQL. Using RECURSIVE, a WITH query can refer to its own output.

The below query creates the fibonacci sequence:

with recursive fib(a, b) AS (

values (0, 1)

union all

select b, a + b from fib where b < 1000

)

select a from fib;

-- 0

-- 1

-- 1

-- 2

-- 3

-- 5

-- ...

ORMs create bad queries

As mentioned in previous sections, ORMs are essentially abstractions built on top of SQL to simplify interactions with your database. Some people use ORMs to write code using the language structures provided by their programming language, rather than crafting SQL queries themselves. The ORM serves as a layer between the relational database and the application, generating the necessary queries.

On the downside, ORMs abstract away database features, can be more challenging to debug than raw queries, and occasionally generate suboptimal queries that are significantly slower than well-written SQL for the same task. One well-known issue is the N+1 query problem.

Let's assume we want to retrieve a blog post along with its comments. A common mistake

we often encounter is the N+1 query problem:

One select query to fetch the post and n additional queries to select

comments for each post (n + 1 queries in total). This is easy

to fix in raw SQL with a simple join. However, when using an ORM, you have less control

on the generated queries, and it can sometimes be challenging to determine

whether you've encountered this problem or not without using a profiler:

-- one query to fetch the posts

select id, title from blog_post;

-- N query in a loop to fetch the comments of each post:

select body from comments where post_id = :post_id;

Stored Procedures

Stored procedures are server-side procedures with names that are typically written in various languages, with SQL being the most common. The following displays the definition of a procedure in SQL:

create procedure insert_person(id integer, first_name text, last_name text, cash integer)

language sql

as $$

insert into person values (id, first_name, last_name);

insert into cash values (id, cash);

$$;

Stored procedures are invoked using the CALL statement:

call insert_person(1, 'Maryam', 'Mirzakhani', 1000000);

One distinguishing feature of PostgreSQL compared to other database systems is that it allows you to write your procedures in any programming language you prefer. This is in contrast to most database engines that restrict you to using only a predefined set of languages.

Additional languages can be easily integrated into the PostgreSQL server

using the CREATE LANGUAGE command:

create language myLovelyLanguage

handler my_language_handler -- the function that glue postgresql with any external language

validator my_language_validator -- check syntax errors before executing function

Functions are a concept similar to stored procedures, but they are distinct entities. Traditionally, people used the term "Stored Procedure" to refer to both, but there are differences between them. One key distinction is that functions can return values, whereas stored procedures do not. However, this is not the only difference.

One of the most significant differences between stored procedures and functions is

that functions can be used within a SELECT statement, but they cannot start or commit

transactions:

select my_func(last_name) from person;

On the other hand, stored procedures can start and commit transactions, but they can not be used inside select statements.

call sp_can_commit_a_transaction();

In short:

- Functions have return values, but stored procedures do not.

- Functions can be used in

selectstatements, but stored procedures do not. - Functions can not start or commit transactions, but stored procedures can.

There's also a concept called Trigger Functions, but we will talk about them when we're

deeper in the ocean!

Cursors

The idea behind CURSOR is that the data is generated only when needed (via a FETCH).

This mechanism allows us to consume the result set while the database is generating

the results. In contrast, it avoids waiting for the database engine to complete its

work and send all the results at once:

declare my_cursor scroll cursor for select * from films; -- you can read more about SCROLL in the collapsible box

fetch forward 5 from my_cursor; -- FORWARD is the direction, PostgreSQL supports many directions.

-- Outputs five rows 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5

-- Cursor is now at position 5

fetch prior from my_cursor; -- outputs row number 4, PRIOR is also a direction.

close my_cursor;

There are no non-nullable types

As mentioned previously, SQL's null is a marker, not a value.

SQL null means unknown, and not having nullable types means we can control the

nullability of columns solely through the use of not null check constraints.

This approach results in flexible data types where any user of the database can input data into the system, even if the data for a column with such a data type is missing or unknown.

PostgreSQL permits the creation of user-defined types using CREATE TYPE, and it's

possible to specify a default for the data type in case a user desires columns of that

data type to default to something other than a null value. However, it remains

valid to set the column value to null if there are no not null check constraints defined.

Optimizers don't work without table statistics

As previously mentioned, PostgreSQL strives to generate an optimal execution plan for your SQL queries. Various plans can produce the same result set, but a well-designed planner/optimizer can produce a faster and more efficient execution plan.

Query optimization is an art of science, and in order to come up with a good plan, PostgreSQL

needs data. PostgreSQL uses a cost-based optimizer which utilizes data statistics, not static rules.

The planner/optimizer estimates the cost of each step in the plan, and picks a plan that

has the least cost for the system.

Additionally, PostgreSQL switches to a Genetic Query Optimizer when the number

of joins exceeds a defined threshold (set by the geqo_threshold variable).

This is because among all relational operators, joins are often the most complex

and challenging to process and optimize.

As a result, PostgreSQL is equipped with a cumulative statistics system which collects and reports information related to the database server activities. These statistics can come in handy for the optimizer. You can read more about the statistics that PostgreSQL collect at The Cumulative Statistics System.

Plan hints

As we already know, PostgreSQL does its best to come up with a good plan execution using statistics, estimates, and guessing. While this approach is generally effective for optimizing user queries, there are situations where users may want to provide hints to the database engine to manually influence certain decisions in execution plans.

These hints can make their way to the planner/optimizer using approaches like

the pg_hint_plan project and adding SQL Comments before the queries:

/*+ SeqScan(users) */ explain select * from users where id < 10;

-- QUERY PLAN

-- ------------------------------------------------------

-- Seq Scan on a (cost=0.00..1483.00 rows=10 width=47)

The comment /*+ SeqScan(users) */ instructs the planner to utilize a sequential

scan when searching for items in the "users" table. Similarly, hints for joins can

be provided using HashJoin(weather city) syntax within the comment.

MVCC Garbage Collection

MVCC stands for Multiversion Concurrency Control. Every database engine needs to somehow manage concurrent access to data, and PostgreSQL as an advanced database engine is no exception. As the name suggests, MVCC is the concurrency control mechanism inside Postgres. Multiversion means that each statement sees it's own version of the database (aka snapshot) as it was sometimes ago. This prevents statements from viewing inconsistent data.

MVCC enables the read and write locks not to conflict with each other, so reading never blocks writing and writing never blocks reading (and PostgreSQL was the first database to be designed with this feature).

Keeping multiple copies/versions of data produces garbage data that takes a lot of space

on the disk which degrades the performance of the database in the long run. Postgres uses

VACUUM to garbage-collect data. VACUUM reclaims storage occupied by dead tuples,

which are tuples that are deleted or obsoleted by an update are not physically

removed from their table. It is necessary to do VACUUM periodically, especially on

frequently-updated tables, hence why PostgreSQL includes an “autovacuum” facility

which can automate routine vacuum maintenance.

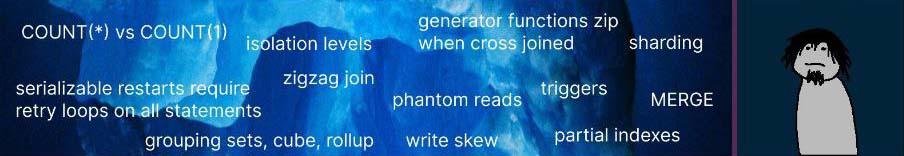

Level 3: Twilight Zone

Welcome to Twilight Zone! Things are starting to get intriguing as we venture into more complex database concepts. Brace yourself for a deeper understanding of PostgreSQL's inner workings.

COUNT(*) vs COUNT(1)

The COUNT function is an aggregate function that can take the form of either count(*)

— which counts the total number of input rows — or count(expression) — which counts the

number of input rows where the value of the expression is not null.

-- Number of all rows, including nulls and duplicates.

-- Performance Warning: PostgreSQL uses a sequential scan of the entire table,

-- or the entirety of an index that includes all rows.

select count(*) from person;

-- Number of all rows where `middle_name` is not null

select count(middle_name) from person;

-- Number of all unique and not-null `middle_name`s

select count(distinct middle_name) from person;

count(1) has no functional difference with count(*) as every row is being counted as

constant 1:

select count(1) from person;

-- equivalent result:

select count(*) from person;

However, an ongoing myth claims that:

using

count(1)is better thancount(*)becausecount(*)unnecessarily selects all the columns.

The above statement ↑ is wrong. In PostgreSQL, count(*) is faster because it is a special

hard-coded syntax with no arguments for the count aggregate function. count(1) is

specifically slower as it follows the count(expression) syntax and it needs to check if constant 1 is

not equal to null for each row.

Isolation Levels and Phantom Reads

As we have mentioned earlier, the I in ACID stands for Isolation. A transaction

must be isolated from other concurrent transactions running in the database.

As an example, when you want to backup your database using tools like pg_dump,

you don't want your backup to be affected by other write operations in the system.

The SQL standard defines 4 levels of transaction isolation. These isolation level are defined in terms of phenomena, and each of these levels either prohibits these phenomena, or does not guarantee of them not happening. The phenomena are listed below:

- dirty read: A transaction reads data written by a concurrent uncommitted transaction.

- nonrepeatable read: A transaction re-reads data it has previously read and finds that data has been modified by another transaction (that committed since the initial read).

- phantom read: A transaction re-executes a query returning a set of rows that satisfy a search condition and finds that the set of rows satisfying the condition has changed due to another recently-committed transaction.

- serialization anomaly: The result of successfully committing a group of transactions is inconsistent with all possible orderings of running those transactions one at a time. Write skew is the simplest form of serialization anomaly.

The four isolation levels in databases are:

Read uncommitted (RU)Read committed (RC)Repeatable read (RR, aka Snapshot Isolation, or Anomaly Serializable)Serializable (aka Serializable Snapshot Isolation)

It's important to note that PostgreSQL does not implement the read uncommitted isolation level.

Instead, PostgreSQL's Read Uncommitted mode behaves like Read Committed.

This is because it is the only sensible way to map the standard isolation levels to

PostgreSQL's multiversion concurrency control architecture.

This approach aligns with the SQL Standard because the

standard defines the minimum guarantees, not the maximum ones. Therefore, PostgreSQL can and does

disallow phantom reads even in the repeatable read isolation level:

| Isolation Level | Dirty Read | Nonrepeatable Read | Phantom Read | Serialization Anomaly |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read uncommitted | ⚠️ Possible (✅ not in PG) | ⚠️ Possible | ⚠️ Possible | ⚠️ Possible |

| Read committed | ✅ Not possible | ⚠️ Possible | ⚠️ Possible | ⚠️ Possible |

| Repeatable read | ✅ Not possible | ✅ Not possible | ⚠️ Possible (✅ not in PG) | ⚠️ Possible |

| Serializable | ✅ Not possible | ✅ Not possible | ✅ Not possible | ✅ Not possible |

Table Guide:

- ✅ N = Not possible

- ⚠️ P = Possible

- ☑️ PnP = Possible, but not in PostgreSQL

| Isolation Level | Dirty Read | Nonrepeatable Read | Phantom Read | Serialization Anomaly |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RU | ☑️ PnP | ⚠️ P | ⚠️ P | ⚠️ P |

| RC | ✅ N | ⚠️ P | ⚠️ P | ⚠️ P |

| RR | ✅ N | ✅ N | ☑️ PnP | ⚠️ P |

| S | ✅ N | ✅ N | ✅ N | ✅ N |

The term "Serializable" execution means that a transaction can run as if it has a "serial execution," where no concurrent operation is affecting it.

Write skew

Write skew is the simplest form of serialization anomaly, and the Serializable isolation level protects you from it. However, the Repeatable Read isolation level does not provide the same protection against write skew.

Assume a table with a column which has either Black or White as the value.

Two users concurrently try to make all rows contain matching color values,

but their attempts go in opposite directions. One is trying to update all white rows

to black and the other is trying to update all black rows to white.

In such a case, two concurrent transactions each determine what they are writing based on reading a data set (rows with black/white column), and that dataset overlaps what the other is writing. In this case we can get a state which could not occur if either had run before the other

If these updates are run serially, all colors will match: one of the transactions

turn all rows to white, and the other turns all rows to black. If they are run concurrently

in REPEATABLE READ mode, the values will be switched, which is not consistent with any

serial order of runs. If they are run concurrently in SERIALIZABLE mode, PostgreSQL's

Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI) will notice

the write skew and roll back one of the transactions.

Read more:

- PostgreSQL's Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI) vs plain Snapshot Isolation (SI)

- PostgreSQL's Serializable Wiki

Serializable restarts require retry loops on all statements

Restarting a serializable transaction requires retry on all the statements of the transaction, not just the failed one. And if the generated transaction on the backend relies on computed values outside of the sql code, those codes needs to be re-executed as well:

// This code snippet is for demonstration-purposes only

let retryCount = 0;

while(retryCount <= 3) {

try {

const computedSpecies = computeSpecies("cat")

const catto = await db.transaction().execute(async (trx) => {

const armin = await trx.insertInto('person')

.values({

first_name: 'Armin'

})

.returning('id')

.executeTakeFirstOrThrow()

return await trx.insertInto('pet')

.values({

owner_id: armin.id,

name: 'Catto',

species: computedSpecies,

is_favorite: false,

})

.returningAll()

.executeTakeFirstOrThrow()

})

continue;

} catch {

retryCount++;

await delay(1000);

}

}

Partial Indexes

A partial index is an index built over a subset of a table specified using a where clause,

and is useful when you know that the column values are unique only in certain

circumstances. One major use-case for partial indexes is for the times that you don't want to

put common items in the index, as their frequent changes can increase the size of index

and slow the index down because of the recurring updates.

As an example, let's assume that most of your customers have the same nationality (at least 25% or so), and there are just a handful of different values in the table, it could be a good idea to create a partial index on the column:

create index nationality_idx on person(nationality)

where nationality not in ('american', 'iranian', 'indian');

Generator functions zip when cross joined

Generator functions, also known as Set Returning Functions (SRF), are functions that can

return more than one row. Unlike many other databases in which only scalar values

can appear in select clauses, PostgreSQL allows set-returning functions to appear in

select. One of the most famous generator functions is the generate_series functions which

accepts start, stop, and step (optional) parameters, and generates a series of values

from start to stop with a step size. This function can generate different types of

series including integer, bigint, numeric, and even timestamp:

select * from generate_series(2,4); -- or `select generate_series(2,4);`

-- generate_series

-- -----------------

-- 2

-- 3

-- 4

-- (3 rows)

select * from generate_series('2008-03-01 00:00'::timestamp,

'2008-03-04 12:00', '10 hours');

-- generate_series

-- ---------------------

-- 2008-03-01 00:00:00

-- 2008-03-01 10:00:00

-- 2008-03-01 20:00:00

-- 2008-03-02 06:00:00

-- 2008-03-02 16:00:00

-- 2008-03-03 02:00:00

-- 2008-03-03 12:00:00

-- 2008-03-03 22:00:00

-- 2008-03-04 08:00:00

-- (9 rows)

In SQL, you can cross join two table using either of these two syntaxes:

select * from table_a cross join table_b; -- with `cross join`

-- or --

select * from table_a, table_b; -- with comma

And for functions, you can call them using either of these two syntaxes:

select * from generate_series(1, 3); -- with `select * from`

-- or --

select generate_series(1, 3); -- with `select` only

Combining these two syntaxes, when we execute the same cross join syntax for generator functions using

select * from f() and select f() syntaxes, one of them turns into a zip operation

instead of a cross join:

select * from generate_series(1, 3) as a, generate_series(5, 7) as b; -- cross joins

-- a b

-- 1 5

-- 1 6

-- 1 7

-- 2 5

-- 2 6

-- 2 7

-- 3 5

-- 3 6

-- 3 7

select generate_series(1, 3) as a, generate_series(5, 7) as b; -- zips

-- a b

-- 1 5

-- 2 6

-- 3 7

In the second case we get the result from two

generator functions side by side (this is called the zip of two results),

instead of a cartesian product. This is because a join plan can not be created

without a from/merge clause (omitted from clause is intended for computing the results

of simple expressions), and PostgreSQL creates a so called ProjectSet node

in the plan to project(display) the items coming from the generator functions.

Sharding

Sharding in database is the ability to horizontally partition data across one more database shards. While partitioning feature allows a table to be partitioned into multiple tables, sharding allows a table to be partitioned in a way so parts of it live on external foreign servers.

PostgreSQL uses the Foreign Data Wrappers (FDW) approach to implement sharding, but it is still in progress.

Citus is an open-source extension for PostgreSQL which enables it to achieve horizontal scalability through sharding and replication. One key advantage of Citus is that it is not a fork of PostgreSQL but an extension, which allows it to stay in sync with the community release. In contrast, many other forks of PostgreSQL often lag behind the community release in terms of updates and features.

ZigZag Join

We've previously discussed logical joins, including left join, right join, inner join,

cross join, and full joins. These joins are logical in a sense that they are simple

joins that we write in our SQL codes. There is another category of joins called physical joins.

Physical joins represent the actual join operations that the database performs to join your data.

These include Nested Loop Join, Hash Join, and Merge Join. You can use explain functionality to see

which kind of physical join your database is using in the plan to execute the logical

join you have defined in your SQL.

ZigZag join is a physical join strategy, and can be thought of as a more performant nested loop join. Assume we have a table like this:

create table vehicle(id integer primary key, tires integer, wings integer);

create index on vehicle(tires);

create index on vehicle(wings);

And we have a select query like this:

select * from vehicle where tires = 0 and wings = 1;

Normally this would be a tough task for a database without a Zig-Zag join, because using one of the secondary indexes and the primary index in our join plan, we still need to fetch many records if we're having such a situation:

- there are many vehicles with tires = 0, or wings = 1

- but not many vehicles with both tires = 0 and wings = 1.

ZigZag join can make use of both indexes to reduce the number of fetched records:

In the zig-zag join shown in the image above, we continually switch between the secondary indexes while comparing with the primary index:

- We first look at the tires index for values of

tires = 0. The firstidis equal to1. Therefore, we need to jump (zig) to the other index and look for rows whereid = 1 (match)orid > 1 (skip). So in general, we jump to the row whereid >= 1. - Zig to the wings index, and as

id = 1, we have found a match. We can safely lookup the next record of the same index. - The next record has the

id = 2. We zag to the tires index whereid >= 2. - The current record has

id = 10. It's not a match, but we've already skipped a lot of records. - We zig to the wings index again, looking for records where

id >= 10 - And so on...

MERGE

Merge conditionally inserts, updates, or delete rows of a table using a data source:

merge into customer_account as ca

using recent_transactions as tx

on tx.customer_id = ca.customer_id

when matched then

update set balance = balance + transaction_value

when not matched then

insert (customer_id, balance)

values (t.customer_id, t.transaction_value);

Using merge we simplify multiple procedural language statements into a single

merge statement.

Triggers

Triggers are a mechanism in PostgreSQL that can execute a function before, after, or

instead of the operation when a certain event is occurred on a table. These events

can be either of insert, update, delete, or truncate.

Trigger functions have access to special variables that store data both before

and after an edit, hence why they are more powerful than check constraints:

create trigger log_update

after update on system_actions

for each row

when (NEW.action_type = 'sensitive' or OLD.action_type = 'sensitive')

execute function log_sensitive_system_action_change();

As you can see, the when clause can refer to columns of the old and/or new row values

by writing OLD.column_name or NEW.column_name respectively.

Grouping sets, Cube, Rollup

Imagine you want to see the sum of the salaries of a different departments based on the

gender of the employees. One way to do this is to have multiple group by clauses and

then union the result rows together:

select dept_id, gender, SUM(salary) from employee group by dept_id, gender

union all

select dept_id, NULL, SUM(salary) from employee group by dept_id

union all

select NULL, gender, SUM(salary) from employee group by gender

union all

select NULL, NULL, SUM(salary) from employee;

-- dept_id gender sum

--

-- 1 M 1000

-- 1 F 1500

-- 2 M 1700

-- 2 F 1650

-- 2 NULL 3350

-- 1 NULL 2500

-- NULL M 2700

-- NULL F 3150

-- NULL NULL 5850

However, this would be a pain if we want to report the sum of salaries for different groups of data. Grouping sets allow us to define a set of groupings and write a simpler query. The equivalent of the above query using grouping sets would be:

select dept_id, gender, SUM(salary) from employee

group by

grouping sets (

(dept_id, gender),

(dept_id),

(gender),

()

);

There are two types of grouping sets, each with its own syntax sugar due to their

common usages: rollup and cube.

rollup (e1, e2, e3, ...)

is equivalent of:

grouping sets (

( e1, e2, e3, ... ),

...

( e1, e2 ),

( e1 ),

( )

)

and

cube ( a, b, ... )

is equivalent of:

GROUPING SETS (

( a, b, c ),

( a, b ),

( a, c ),

( a ),

( b, c ),

( b ),

( c ),

( )

)

Grouping sets can also be combined together:

group by a, cube (b, c), grouping sets ((d), (e))

-- equivalent:

group by grouping sets (

(a, b, c, d), (a, b, c, e),

(a, b, d), (a, b, e),

(a, c, d), (a, c, e),

(a, d), (a, e)

)

Level 4: Midnight Zone

Welcome to Midnight Zone! In this level, we'll delve into the depths of PostgreSQL. Prepare to navigate the challenges and professional topics of a modern database system.

Denormalization

One of the first steps of designing a database application is going thorough the normalization process (1NF, 2NF, ...) in order to reduce data redundancy and improve data integrity. Even though relational database, specially Postgres, are well optimized for having many primary keys and foreign keys in tables, and are capable of joining between many tables and handling many constraints, a heavily normalized schema might still be challenging to deal with because of performance penalties.

In such a scenario, if maintaining a fully normalized table becomes challenging, the database designer can go thorough a process known as denormalization. In other words, it improves the read performance of your data, with the cost of reducing the write performance, as you may need to write multiple copies of your data.

PostgreSQL natively supports many denormalized data types including array, composite types

created via create type, enum, xml, and json types. Materialized views are

also used to implement faster reads with slower writes trade-off.

A materialized view is a view that is stored on disk.

You can create a denormalized and materialized view of your data for fast reads, and then

use refresh materialized view my_view to refresh this cache.

NULLs in CHECK constraints are truthy

As we have mentioned earlier, null in SQL means not knowing the value,

rather than the absence of a value, and such a select will return null:

select null > 7; -- null

If we create a column with a check constraint on it like this:

create table mature_person(id integer primary key, age integer check(age >= 18));

and then we try to insert a row where the age equals 15, we will get this error:

ERROR: new row for relation "mature_person" violates check constraint "mature_person_age_check"

DETAIL: Failing row contains (1, 15).

However, this insert will succeed:

insert into mature_person(id, age) values (1, null)

-- INSERT 0 1

-- Query returned successfully in 80 msec.

It might not make sense to assume something satisfies a check constraint when you

don't know the value of it (null), but in SQL we have to let the row thorough because

nulls in check constraints are truthy.

Transaction Contention

Resource contention is a conflict over access to a shared resource like RAM, network interface,

storage, etc. In case of SQL databases, a resource contention can appear in form of

transaction contentions, and that is when multiple transactions want to write to a

row at the same time. A transaction contention might require delays, retries, or halts to fix

as they might cause deadlocks/livelocks. This is actually configurable using the deadlock_timeout

config.

A contention usually slows down your database without leaving many clues for you to debug them, and the negative effect gets worse when you have multiple nodes or clusters. That being said, projects like Postgres-BDR might provides tools to diagnose and correct contention problems.

SELECT FOR UPDATE

select clause is used to read data from database, but sometimes you want to select

rows in order to write them. If any of the below lock strengths are specified:

select ... for updateselect ... for no key updateselect ... for shareselect ... for key share

the select statement locks the entire selected rows (not just the columns) against

concurrent updates:

begin;

select * from users WHERE group_id = 1 FOR UPDATE;

update users set balance = 0.00 WHERE group_id = 1;

commit;

This is sometimes known as pessimistic locking. You should be careful when using explicit locking, because if you perform long-running works in a transaction, the database will lock the rows for the entirety of time:

begin;

select * from users WHERE group_id = 1 FOR UPDATE; -- rows will remain locked and cause performance degradation

-- doing a lot of time consuming calculations

update users set balance = 0.00 WHERE group_id = 1;

commit;

You can switch to optimistic locking in such cases. Optimistic locking assumes that others won't update the same record and verifies this during update time, rather than locking the record throughout the entire processing duration on the client side.

timestamptz doesn't store a timezone

If we run this query:

select typname, typlen

from pg_type

where typname in ('timestamp', 'timestamptz');

-- typname typlen

-- timestamp 8

-- timestamptz 8

we will realize that timestamp and timestamp with time zone types have the same size,

which means PostgreSQL doesn't actually store the timezone for timestamptz. All it does

is that it formats the same value using a different timezone:

select now()::timestamp

-- "2023-08-31 16:56:54.541131"

select now()::timestamp with time zone

-- "2023-08-31 16:56:58.541131"

set timezone = 'asia/tehran'

select now()::timestamp

-- "2023-08-31 16:56:54.541131"

select now()::timestamp with time zone

-- "2023-08-31 16:56:23.73028+04:30"

- Read more: The Long, Painful History of Time by Erik Naggum

- Watch: The Problem with Time & Timezones - Computerphile

Star Schemas

Star schema is a database modeling approach adopted by relational data warehouses. It requires modelers to classify their model tables as either dimension or fact. The star schema consists of one or more fact tables referencing to any number of dimension tables.

In data warehousing, a fact table consists of measurements, metrics or facts of a business process, while a dimension table is a structure that categorizes facts and measures in order to enable users to answer business questions. Commonly used dimensions are people, products, place and time.

Sargability

In relational databases, a condition (or predicate) in a query is said to be sargable if the DBMS engine can take advantage of an index to speed up the execution of the query. The ideal SQL search condition has the general form:

<column> <comparison operator> <literal>

A common thing that can make a query non-sargible is using an indexed column inside a function, for example using this query:

select birthday from users

where get_year(birthday) = 2008

instead of the equivalent sargible one:

select birthday from users

where birthday >= '01-01-2008' AND birthday < '01-01-2009'

Or as another example:

select *

from players

where SQRT(score) > 7.5

SARG is a contraction for Search ARGument. In the early days, IBM researchers named these kinds of search conditions "sargable predicates". In later days, Microsoft and Sybase redefined "sargable" to mean "can be looked up via the index."

Ascending Key Problem

Assume that we have such a time-series event table:

create table event(t timestamp primary key, content text);

In this situation, the primary key or index of such tables are continuously increasing over time and the rows are always being added to the end of table. This can result in data fragmentation as the end of the table is the only spot being written, and the inserting point is not evenly distributed among the rows.

This can lead to various issues, such as contention at the end of the table, making it challenging to distribute and shard the table, and slower data retrievals due to the lack of table statistics at the end.

As mentioned earlier, a database system relies on statistics to generate more

optimal execution plans. It's important to note that statistics for the most

recently inserted rows are not included in the database statistics, e.g. pg_stat_database.

One way to fix the ascending key problem in PostgreSQL is to use the block range index (BRIN index).

These indexes give performance improvements when the data is naturally ordered as it

is added to the table, such as t timestamp columns or a naturally auto incremented columns.

create table event (

event_time timestamp with time zone not null,

event_data jsonb not null

);

create index on event using BRIN (event_time);

Ambiguous Network Errors

Various types of network errors can occur when working with databases, such as disconnecting from the database during a transaction. In such cases, it's your responsibility to verify whether your interaction with the database was successful or not.

Ambiguous network errors may not provide clear indications of where the process was

interrupted, or even if a network problem exists. If you are running a streaming replication,

a young connection in the pg_stat_replication table might be a sign of a network problem or

other kind of reliability issues.

utf8mb4

utf8mb4 stands for "UTF-8 Multibyte 4" and is a MySQL type. It has nothing to do with

PostgreSQL or the SQL standard.

Historically, MySQL has used utf8 as an alias for utf8mb3. That means that it can

only store Basic Multilingual Plane unicode characters (3 byte unicode characters).

If you want to be able to store all unicode characters, you need to explicitly use

utf8mb4 type.

Beginning with MySQL 8.0.28, utf8mb3 is used exclusively in the output of show statements and in

Information Schema tables when this character set is meant.

At some point in the MySQL history utf8 is expected to become a reference to utf8mb4.

To avoid ambiguity about the meaning of utf8, MySQL users (and MariaDB users, because

MariaDB is a fork of MySQL) should consider specifying utf8mb4 explicitly

for character set references instead of utf8.

Level 5: Abyssal Zone

Welcome to Abyssal Zone! Here, we'll explore the abyss of PostgreSQL's concepts. Things that you might haven't heard before!

Cost models don't reflect reality

When explaining a query, you can enable the "cost" option, which provides you with the estimated statement execution cost. This cost represents the planner's estimate of how long it will take to execute the statement, typically measured in cost units, conventionally indicating disk page fetches.

The planner uses the table statistics to come up with the best plan it can with the lowest cost. However, that computed cost can be utterly wrong as it's just an estimated value, or could be based on the wrong statistics (as we've seen in the ascending key problem).

'null'::jsonb IS NULL = false

NULL in SQL means not knowing the value, while JSON's null is JavaScript's null and

represents the intentional absence of any value. This is why JSON's null in

PostgreSQL's jsonb data-type is not equivalent to SQL's null:

select 'null'::jsonb is null;

-- false

select '{"name": null}'::jsonb->'name' is null;

-- false, because JSON's null != SQL's null

select '{"name": null}'::jsonb->'last_name' is null;

-- true, because 'last_name' key doesn't exists in JSON, and the result is an SQL null

TPCC requires wait times

TPC-C stands for "Transaction Processing Performance Council - Benchmark C" and is an online transaction processing benchmark hosted at tpc.org. TPC-C involves a mix of five concurrent transactions of different types and complexity either executed on-line or queued for deferred execution. The database is comprised of nine types of tables with a wide range of record and population sizes. TPC-C is measured in transactions per minute (tpmC).

TPC-C benchmarks includes two type of wait times: The keying time represents the time spent entering data at the terminal (pressing keys on the keyboard) and the think time represents the time spent, by the operator, to read the result of the transaction at the terminal before requesting another transaction. Each transaction has a minimum keying time and a minimum think time.

These times will help the benchmark to be closer to real-world scenarios. Benchmarking transactions without wait-time will make the system under test slower and slower overtime as the system internals will have no free resources to operate.

pgbench is the command-line tool used to benchmark PostgreSQL databases, and it supports TPC and

many different command-line arguments including wait-time/schedule-lag-time.

DEFERRABLE INITIALLY IMMEDIATE

Constraints on columns can be either deferred or immediate.

Immediate constraints are checked at the end of each statement, while deferred constraints are

not checked until transaction commit. Each constraint has its own IMMEDIATE or DEFERRED mode.

Upon creation, a constraint is given one of three characteristics:

not deferrable(default, equivalent toimmediate): the constraint is checked immediately after each statement. This behavior can NOT be changed using theset constraintcommand. e.g.set constraint pk_name deferred;deferrable initially immediate: the constraint is checked immediately after each statement, however, this behavior can later be altered using theset constraintcommand.deferrable initially deferred: the constraints are not checked until transaction commit. This behavior can later be altered using theset constraintcommand.

create table book (

name text primary key,

author text references author(name) on delete cascade deferrable initially immediate;

)

As you see in the SQL code above, deferrable initially immediate is specified while

defining the schema of the table, not on runtime.

EXPLAIN approximates SELECT COUNT(*)

Using explain with select count(*) can give you an estimate of how many rows PostgreSQL

think are in your table using table statistics.

explain select count(*) from users;

If you don't need an exact count, the current statistic from the catalog table

pg_class might be good enough and is much faster to retrieve for big tables:

select reltuples as estimate_count from pg_class where relname = 'table_name';

MATCH PARTIAL Foreign Keys

match full, match partial, and match simple(default) are three table column

constraints for the foreign keys. Foreign keys are supposed

to guarantee the referential integrity of our database, and in order to do so, database

needs to know how to match the referencing column value with the referenced column value

in case of nulls.

match full: will not allow one column of a multi-column foreign key to benullunless all foreign key columns arenull; if they are allnull, the row is not required to have a match in the referenced table.match simple(default): allows any of the foreign key columns to benull; if any of them arenull, the row is not required to have a match in the referenced table.match partial: if all referencing columns arenull, then the row of the referencing table passes the constraint check. If at least one referencing columns is not null, then the row passes the constraint check if and only if there is a row of the referenced table that matches all the non-null referencing columns. This is not yet implemented in PostgreSQL, but a workaround is to usenot nullconstraints on the referencing column(s) to prevent these cases from arising.

Causal Reverse

Causal reverse is a transaction anomaly that can be encountered even with Serializable isolation levels. To address this anomaly, a higher level of serializability known as Strict Serializability is required.

Here is a simple example for the causal reverse anomaly:

- Thomas executes

select * from events, doesn't get a respond yet. - Ava executes

insert into events (id, time, content) values (1, '2023-09-01 02:01:16.679037', 'hello')and commit. - Emma executes

insert into events (id, time, content) values (2, '2023-09-01 02:02:56.819018', 'hi')and commit. - Thomas gets the respond of the

selectquery from step 1. He gets the Emma's row, but not Ava's.

In the causal reverse anomaly, a later write which was caused by an earlier write, time-travels to a point in the serial order prior to the earlier write.

Level 6: Hadal Zone

Welcome to Hadal Zone! As we reach extreme depths, we'll discuss specialized PostgreSQL topics like learned indexes, TXID Exhaustion, and more!

Vectorized doesn't mean SIMD

SIMD stands for "Single instruction, multiple data", and is a type of parallel processing when a single CPU instruction is simultaneously applied to multiple different data streams.

The term "Vector" and "Vectorized" usually come with the term "SIMD" in computer literature. Vector programming (aka Array programming) refers to solutions that allow us to apply operations to an entire set of values at once. As a matter of fact, the extension instruction set which was added to the x86 instruction set architecture to perofrm SIMD is called Advanced Vector Extensions (AVX).

SIMD is one approach to leverage vector computations and not the only way. That being said, PostgreSQL vectors are backed by SIMD cpu instructions.

NULLs are equal in DISTINCT but unequal in UNIQUE

Assume you have a table called unique_items with such a definition:

create table unique_items(item text unique);

PostgreSQL will prevent you to insert duplicate 'hi' values, as the second one

would violate the unique constraint:

insert into unique_items values ('hi');

-- INSERT 0 1

-- Query returned successfully in 89 msec.

insert into unique_items values ('hi');

-- ERROR: duplicate key value violates unique constraint "unique_items_item_key"

-- DETAIL: Key (item)=(hi) already exists.

However, we can insert as many nulls as we want:

insert into unique_items values (null); -- INSERT 0 1; Query returned successfully

insert into unique_items values (null); -- INSERT 0 1; Query returned successfully

insert into unique_items values (null); -- INSERT 0 1; Query returned successfully

table unique_items;

-- item

--

-- "hi"

-- `null`

-- `null`

-- `null`

This means that to SQL, null values are not the same, as they are unknown values.

But now if we select distinct items of the unique_items table, we will get this result:

select distinct item from unique_items;

-- item

--

-- `null`

-- "hi"

All of the null values are shown as a single item, as if PostgreSQL grouped all the unknown

values in one value.

Volcano Model

"Volcano - An Extensible and Parallel Query Evaluation System" is a research paper by Goetz Graefe that was published in the IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering (Volume: 6, Issue: 1) on February 1994. This evaluation system is called Volcano Model, Volcano iterator model, or sometimes simply referred to as the Iterator model.

Each relational-algebraic operator produces a tuple stream, and a consumer can iterate

over its input streams. The tuple stream interface is essentially: open, next, and

close; all operators offer the same interface, and the implementation is opaque.

Each next call produces a new tuple from the stream, if one is available.

To obtain the query output, one "next-next-next"s on the final RA operator;

that one will in turn use "next"s on its inputs to pull tuples allowing it to

produce output tuples, etc. Some "next"s will take an extremely long time, since many

"next"s on previous operators will be required before they emit any output.

Example: select max(v) from t may need to go trough all of t in order to find that

maximum.

A highly simplified pseudocode of the volcano iteration model:

define volcano_iterator_evaluate(root):

q = root // operator `q` is the root of the query plan

open(q)

t = next(q)

while t != null:

emit(t) // ship current row to application

t = next(q)

close(q)

Join ordering is NP Hard

When you have multiple joins in your SQL query, the database engine needs to find an order to perform the joins. Finding the best join order is an NP-hard problem. This is why database engines use estimates, statistics, and soft computing approaches to find an order since finding the optimal solution would take forever.

This is a simplified table of problem classes:

| Problem Class | Verify Solution | Find Solution | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| P | 😁 Easy | 😁 Easy | Multiply numbers |

| NP | 😁 Easy | 😥 Hard | 8 Queens |

| NP-hard | 😥 Hard | 😭 Hard | Best next move in Chess |

NP-hard problems are at least as hard as the hardest problems in NP. That means if P ≠ NP (which is probabely the case, at least for now), NP-hard problems could not be solved in polynomial time.

If P=NP, then the world would be a profoundly different place than we usually assume it to be. There would be no special value in “creative leaps,” no fundamental gap between solving a problem and recognizing the solution once it's found. Everyone who could appreciate a symphony would be Mozart; everyone who could follow a step-by-step argument would be Gauss; everyone who could recognize a good investment strategy would be Warren Buffett.

- Scott Aaronson

Database Cracking

Cracking is a technique that shifts the cost of index maintenance from updates to query processing. The query pipeline optimizers are used to massage the query plans to crack and to propagate this information. The technique allows for improved access times and self-organized behavior.

In other words, Database cracking is an approach for data indexing and index maintainance in

a self-organized way. In a database system where database cracking is used, an

incoming query requesting all elements which satisfy a certain condition c does not

only return a result but it also causes a reodering of the physical database so that

all elements satisfying c are stored in a contiguous memery space. Therefore the

physical database is devided into multiple parts (cracked).

By using this mechanism the database reorganizes itself in the most favourable way according to the workload which is put on it.

- Read more: Database Cracking by David Werner

WCOJ

Traditional binary join algorithms such as hash join operate over two relations

at a time (r1 join r2); joins between more than two relations are implemented by

repeatedly applying binary joins (r1 join (r2 join r3)).

WCOJ (Worst-Case Optimal Join) is a kind of join algorithm whose running time is worst-case optimal for all natural join queries, and is asymptotically faster in worst case than any join algorithm based on such iterated binary joins.

- Read more: Worst-case Optimal Join Algorithms

Learned Indexes

Learned Indexes are indexing strategies that utilize artificial intelligence approaches and deep-learning models to outperform cache-optimized B-Trees and reduce memory usage. Google and MIT engineers developed such a model and published their work as a pioneer paper with the title "The Case for Learned Index Structures". The key idea is that a model can learn the sort order or structure of lookup keys and use this signal to effectively predict the position or existence of records.

- Read more: The Case for Learned Index Structures

TXID Exhaustion

Transaction ID Exhaustion, often referred to as the "Wraparound Problem," arises due to the limited number of transaction IDs available and the absence of regular database maintenance, known as vacuuming.

PostgreSQL's MVCC transaction semantics depend on being able to compare transaction ID (XID) numbers: a row version with an insertion XID greater than the current transaction's XID is “in the future” and should not be visible to the current transaction. But since transaction IDs have limited size (32 bits) a cluster that runs for a long time (more than 4 billion transactions) would suffer transaction ID wraparound: the XID counter wraps around to zero, and all of a sudden transactions that were in the past appear to be in the future — which means their output become invisible. In short, catastrophic data loss. (Actually the data is still there, but that's cold comfort if you cannot get at it.)

To avoid this, it is necessary to vacuum every table in every database at least once every two billion transactions.

Level 7: Pitch Black Zone

Welcome to Pitch Black Zone! Congratulations on your journey to the deepest reaches of PostgreSQL knowledge. Brace yourself for esoteric and cutting-edge topics, where only the boldest dare to venture!

The halloween problem

Halloween Problem is a database error that a database system developer needs to be aware of.

On the Halloween day of 1976, a couple of computer engineers were working on a query that was supposed to give a 10% raise to every employee who earned less than $25,000:

update employee set salary = salary + (salary / 10) where salary < 25000